Introduction

The year 2009, was the birth centenary year of my father, Dr. Purushottam Kashinath Kelkar, known to many in India and abroad as the first founder director and architect of the highly regarded Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, India. His success as the director of not just IIT Kanpur, but also IIT Bombay (of which he had previously been the planning officer and deputy director), made him a legend in his time in the field of technical education in India.

A quiet, self-effacing person, most people knew my father in his professional capacity. Hence I thought it would be good to collect personal memories of him from his colleagues and relatives. I am presenting them here with a brief history of his career. Included also are my own recollections of this charming and gentle personality, who had such an impact on the educational scene in India. In what follows I have referred to him as PKK for the sake of convenience.

Childhood and Education

PKK was born on June 1, 1909, in Dharwar, Karnataka, India. His father, Kashinath Hari Kelkar, was a professor of philosophy in the Bombay Presidency(1), the regional colonial-political administrative unit. He was, therefore, subject to transfers within the area. As a result, PKK received his elementary and secondary education in Bombay and Poona.

Some memories of his childhood days from his cousins give us a glimpse of the future educator. As a young girl, one of his cousins had learned how to make a doll from a square piece of cloth. The day she tried to show off her skill to PKK she was not able to make the doll and started crying. After PKK let her have her cry, he put his hand over her shoulders and said, “Do you know why things went wrong? You wanted to show off to me how you can make the doll. On the other hand, if you made the doll just for pleasure, you would have done it right.” This made her feel much better. Her brother had a different experience. He did not do well on his first year exam, he was afraid of being taken to task. In his characteristically soft-spoken manner PKK said, “The first year exam should have been very easy had you worked at your full potential.” The cousin was taken aback by the response and marveled at the stern warning he received in those gentle words. That was the way PKK dealt with his young cousins, kind and yet firm. Later, when his cousins were of university age, he encouraged them to take science courses.

From his childhood PKK was interested in public speaking and earned prizes in elocution competitions. At the age of 11, he was moved to make an extempore speech at the funeral of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a national leader in the Indian independence movement.

PKK graduated with honors in Physics in 1931 from the then Royal Institute of Science, Bombay. The next year he joined the Indian Institute of Science (IISc.) in Bangalore. He obtained the Diploma in Electrical Engineering in 1934. After that, instead of taking a job in industry, he decided to further his education.

He joined the University of Liverpool as a Ph.D. student. This was possible because of a scholarship from the Ichalkaranji Trust, which was established for financing deserving students. His subject for Ph.D. involved acoustical measurement and the performance of synchronous machinery on load. He completed his Doctorate in Electrical Engineering in 1937, under the guidance of Dr. J.C. Prescott. Just before finishing his doctoral work there was a fire in the laboratory. PKK lost a lot of his data and had to do the work all over again. He also lost his only warm jacket to the fire and Laboratories of Applied Electricity at the University were gracious enough to replace it at a later date. After getting his Ph.D., he worked at Metropolitan Vickers as an intern in power systems.

First Job - Lecturer at Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore

PKK returned to India soon afterwards and joined his alma mater, IISc., as Lecturer in Electrical Engineering from 1937 to 1943. While he was there, he edited a newsletter for the electrical engineering department. Among his colleagues were well known physicists like Nobel Laureate C.V. Raman, Homi Bhabha, and Vikram Sarabhai. However, it seems that the politics of the Institute was not favorable to his growth and success.

Head of Electrical Engineering, Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute, Bombay

In 1943, he accepted the post of Professor and Head of the Department of Electrical Engineering at the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute in Bombay (VJTI), where he continued until 1956. Some of his colleagues like Professor Char(2), who knew PKK from Bangalore, thought it was a step down in going from a research institution like Indian Institute of Science to a diploma engineering college like VJTI.

Char fondly remembered the interviewing technique he learned from PKK. The purpose of an interview is not just to list the skills and knowledge the candidates possess, but also how these would be put to use in helping with the current needs and growth of the department in particular and the institution as a whole. Char believes that a number of PKK’s ideas, such as the purchase of high voltage equipment for VJTI and his vision for a science based engineering institution, may have been formed during his tenure at IISc. Bangalore.

PKK’s tenure at VJTI proved to be a fruitful period for the Institute, thanks to a series of initiatives through which he sought to modernize and update the Electrical Engineering Department.The first degree-granting program in Electrical Engineering was started at VJTI in 1947, through its recent affiliation with Bombay University. (Before this, the Institute only awarded diplomas in various engineering disciplines.) PKK was also responsible for establishing a Master’s degree program in Electrical Engineering. Perhaps even more significantly, PKK started a high-voltage equipment-testing laboratory - the only one in and around Bombay, thus facilitating a liaison between industry and the technical institute. In addition, he ensured that the VJTI library was of high quality and included the latest engineering periodicals on its shelves.

Since PKK had a Ph.D. in electrical engineering (which was rare in those days), students were a little intimidated by the mere aura exuded by this silk suit clad, calm person with a ready smile. Other professors used chalk and board to draw diagrams and write points, while PKK used them only to explain some ideas if a student asked a question. From beginning to end he spoke in a quiet voice in flawless English. The students had to concentrate very hard to hear him well. One of his students, Mr. A. V. Pandit, mentioned that he and other students referred to PKK’s lectures in electrical engineering as “Electrical Poetry.”

An example of PKK's subtle sense of humor was provided by Dr. Arvind Dighe(3) who was the secretary and coordinator of a party arranged for seniors of the mechanical engineering department at VJTI. At the event, Dighe sat between Kelkar and the principal of VJTI, Mr. B.B. Sengupta. When the snacks were served, PKK quietly passed one snack to the next person and another snack to Dr. Dighe. Dighe pointed out to Mr. Sengupta what PKK was doing. Mr. Sengupta quipped, “Look, he is a professor of electrical engineering, knows only transmission and distribution and no consumption.” PKK rejoined, “Yes that is why my machines always have efficiencies above 95%, unlike mechanical machines.”

Inception of the Indian Institutes of Technology

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, realized that newly independent India would progress more quickly in the fields of science and technology through collaborations with the advanced nations of the world. Nehru conceived of and established the system of Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) in different regions of India. They were originally envisioned by the Sarkar Committee in the late Imperial period. The post-independence IITs would be engaged in Research and Development in science and engineering in addition to teaching. The first IIT was established in 1953 at Kharagpur in West Bengal. Nehru then secured collaboration with the USSR through UNESCO for IIT Bombay, the second institute within the IIT system. PKK was a member of the joint India-UNESCO Mission, which visited the USSR in 1955, with the other members of the mission.

Planning Officer for IIT Bombay

PKK was appointed as Planning Officer for IIT Bombay (IITB) in 1956, and later became its Deputy Director. He had good rapport and working relationship with the team leader, Professor Vladimir Martinovsky. A group of Russian experts collaborated on the initial development of IITB, staying in Bombay for about three years. During his tenure at IIT Bombay, PKK witnessed the first class of students admitted in 1958, and when the first Faculty appointments were made about 80 individuals joined.

During this period of his life, I recall how much he enjoyed planning banquets for the visiting professors, and their spouses, and other guests. PKK was an avid connoisseur of fine cuisine. Most of these parties were arranged at restaurants of well-known hotels, since his apartment was small. On returning home he would regale us children with descriptions of decorations, seating arrangements, and mouth-watering delicacies on the menu, often bringing back some leftover pastries from the spread of desserts.

Having established the institute from the beginning, PKK was very disappointed to learn in late 1958 of the appointment of someone else as Director of IITB, who would assume directorship in January of the following year. He thought of returning to his professorship at VJTI but stayed on when the Education Ministry informed him that he was being considered for the directorship of other IITs. In November 1959, the Ministry appointed him Member Secretary of the Postgraduate Committee, which was commissioned to study postgraduate education and research in engineering and technology in India. PKK saw his appointment as an exciting research opportunity, which would bring him in contact with the engineering institutions around the country.

Appointment as Director of IIT Kanpur

Immediately after that, however, PKK was appointed Director of IIT Kanpur (IITK) in December 1959, and he assumed charge in the middle of the month. He realized that he was entirely on his own when he arrived in Kanpur. He remembered his friend’s comment that taking this job was like “committing professional suicide.” Years later, in his memoirs, he would write, “There was no looking back. History took hold of me and generated in me a compulsive feeling to push forward ‘Project IIT Kanpur’ for all it was worth, as though it was a historical necessity. From that time onwards I went about taking a number of unusual steps to move ahead in the interest of the project, as a man possessed.”

PKK’s vision of IITK

According to A.S. Parasnis(4), PKK’s vision of IITK would be an academic institution conscious of responsibility and accountability, with an open, informal, and flexible atmosphere. The Institute would have an engineering curriculum based on science, humanities and social sciences, with faculty equally engaged in teaching and research. According to this vision, collective decision-making would be of vital importance, requiring close interaction among all departments, faculty, students, and supporting staff. PKK’s thorough study of educational systems around the world was the source of his educational philosophy, much of which was subsequently adopted by the rest of the IIT system and other Indian universities.

An open campus, with the towering library positioned at its center for maximum accessibility was PKK’s vision of an academic institution. The choice of the architect A. P. Kanvinde(5) for the departmental buildings was deliberate. According to PKK, Kanvinde was “sensitive to academic needs arising out of new ideas, new perspectives, new vision, and the spontaneous exercise of freedom of thought, speech, and sometimes action on the part of the faculty and the student body”. Kanvinde was successful in using local material to create “Beauty, Comfort, and Delight” through his imaginative design. PKK said, “Kanvinde created a structure that was a symbol of harmony between form, function, and the landscape. It soon became obvious to us that he too was ‘infected’ by the spirit of IIT Kanpur.”(6)

Kanvinde said that as a result of his association of over ten years with PKK and IITK he learned about a different way of looking at the architecture of academic buildings. He realized how it was an integral part of the educational philosophy: the open architecture was to be representative of the interdependence and cooperation of faculty from different academic disciplines, students, and the administration. Kanvinde was very pleasantly surprised by the concept. He was used to monumental, multi-storied, block-form buildings comprising all departments. The buildings remained rigid over the course of time, where no expansion was possible. The ideology promoted by PKK was a departure from the one represented by other institutions built before IITK. Mr. Russell Wood, a New York architect, collaborated with Kanvinde during the design phase of the architecture of the institute. This novel architectural experiment was well received by the architectural profession in India and abroad. Architecture of IITK was a featured exhibit by the Architectural League of New York.

In fact, PKK’s primary objective was to establish an institution devoted to the pursuit of academic excellence. All the departments - engineering, science, mathematics, and humanities - would have the same academic and institutional status. The core curriculum of the institute was designed to include courses in the sciences, engineering science, social sciences, and humanities. PKK expected the student graduating from IITK to be not just a technocrat, but a sensitive cultured human being appreciative of the humanities and the arts, and cognizant of his or her responsibility to society.

An unconventional recruitment process

A remarkable faculty was successfully recruited by PKK for IITK. The recruitment process began in August 1960, with the creation of faculty selection committees according to specifications of the Parliament Act. PKK perceived that the selection of a candidate by committee based primarily on interviews - which was the standard practice at the time - would not necessarily recruit the kind of faculty he envisioned for IITK. To this end, the Director and his colleagues gathered detailed information on each candidate, subtly making a case for those candidates preferred by the institute’s administration. The chairman of the board of governors of IITK Mr. C. B. Gupta, governor of the State of Uttar Pradesh, had his representative on the selection committees as it was mandatory.

PKK acted with the firm conviction that IITK would be a leading institution for technical education and this inspired many candidates to accept IITK positions. These candidates were “young highly qualified individuals, enthusiastic and full of adventure. Most of them had given up satisfying and remunerative jobs abroad and decided to involve themselves in the great adventure of building up IIT Kanpur.”(7). Dr. M.S. Muthana, Deputy Director IITK, was responsible for the infrastructure of IITK. This included the operation and maintenance of the campus which included the staff of the various buildings, hostels, messes, etc. This allowed PKK to concentrate on the setting up of the educational systems that he wanted for the future.

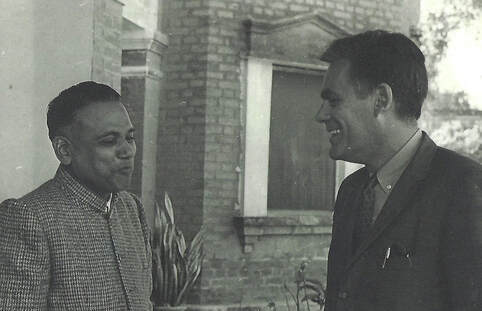

Dr. P.K. Kelkar and Dr. Norman C. Dahl

The Kanpur Indo-American Program

The collaborative program between IITK and a consortium of nine American universities called the Kanpur Indo-American Program (KIAP) played an important role in the development of the institute. According to Dr. Norman C. Dahl, a three-man MIT committee visited India in January 1961 to identify a suitable institution for extensive assistance from MIT. The initial skepticism of the delegation from USA was soon replaced by great enthusiasm after they met and spent time with PKK in Kanpur. They found in him an educator who both understood and shared their vision, and one of them commented, “You see he worships the same gods that we do.” As PKK had studied the question of how science and technology might contribute to the growth of India, he had concluded that the development of universities was essential. The committee agreed with PKK that a total involvement of students and faculty in intellectual and scholastic pursuits relevant to the national goals and aspirations of India should characterize such universities.(8) A Steering Committee formed by the nine consortium universities appointed Dahl from MIT as the first program leader.

Professor Emeritus Robert Green, Ohio State University, met PKK in Boston in 1961. He found an unassuming gentleman who immediately showed a grasp of the essentials of comprehensive university education. It was evident at the Steering Committee meeting that PKK had the ability to look forward and not backward. The Steering Committee along with Mr. Green met PKK at IITK. The KIAP program leader would be an advisor to the Director. The IITK faculty would be responsible for and in charge of the educational program and visiting faculty would act in an advisory capacity under the leadership of the program leader.

In 1963-1964, the faculty selection committees were considering applications of candidates from abroad without personal appearance at committee sessions. It was also the year when the first few of the new IITK faculty members arrived from overseas. The committees chaired by PKK always included a representative of the non-academic community. These off-campus committee members did not understand how candidates could be selected if they were not present at the interview. PKK had the advantage of knowing that these candidates had usually been interviewed by members of the steering committee who had communicated their findings to him. PKK had the delicate task of convincing the off-campus committee members, and in some cases, the junior IITK faculty applicants of the fairness of the process. He did this with his usual grace, reaching consensus on selections without dictating the result. Professor Green was the second program leader of Kanpur Indo-American Program (KIAP) after Dahl.

Gradually, department chairmen were selected. During Green’s second year as Program Leader, organizational changes were made. A new type of organization not commonly found in Indian institutions was established. The Dean of Research and Dean of Faculty were both appointed by the Director.

According to Professor Green, PKK led IITK to prominence, with graduates of international standards, in the shortest possible time. IITK graduates have distinguished themselves in every field of endeavor and continue to occupy faculty positions in all the consortium universities. Professor Green felt that it was a privilege to have known PKK.

Throughout his association he found PKK to be somewhat formal, but friendly. Green recalls a number of meetings with PKK where they discussed a variety of topics. He had been struck by the fact that PKK never made a note of future meetings but was always prompt in attending them. In contrast, Green always carried an appointment book.

The Campus School

PKK not only wanted to establish a world-class institute of technology, but also wanted an excellent elementary school for the children of faculty members and other staff. In this connection he requested Mrs. Meera Parasnis (wife of Dr. A.S. Parasnis and an experienced science teacher) to chair a committee including Mrs. Dorothy Dahl (wife of Norman C. Dahl) and other faculty wives. The following letter refers to the Campus School as the school and the related problems encountered in securing funds for the recruitment of teachers and its operation.

In his letter to Norman Dahl dated July 2nd, 1964, PKK says, “I must confess that I find life here incomplete because of your absence. I did not realize when you left how much I had taken your being here for granted. I know that the only response to the situation is acceptance. All the same, time does drag. The present seems too much tied down to the past to take much notice of the future. Autumn leaves make it difficult to think of spring that is yet to be.”

“I am sure Mrs. Dahl will be pleased to know that the Ministry has sanctioned the school scheme for one year in the first instance. That means we begin as we wanted to. Mrs. Parasnis is all in it, and I have every hope that we will make good progress. Some teachers have been recruited, and more will be recruited next week. And so we continue to be on the road of our choice.”

In his August 4th, 1964 letter to Dahl, PKK says, “Both the school and the Institute opened on the 15th of July. The school has been a great success so far, and it means another burden for me. This is a worst feeling within oneself that although there are hundred ways of doing things there is only one right way. The school seems to have some of the characteristics of a computer. It just leads us and we have to follow. Let us see where we go from here. On the opening day particularly, I missed your presence as I did that of Mrs. Dahl. I am still not accustomed to your not being here, but the momentum you helped in generating is carrying us forward, and I have a feeling that every day there is an addition to it in some form or another.

The Campus School is growing beyond expectations. There are nearly 500 children in the school and the number of teachers has exceeded 25. The Central School is also progressing reasonably well. The most interesting thing is that although the Central School is paying much higher salaries to their teachers, the teachers we have in the Campus School are far better in quality, and they have enthusiasm for teaching. The reason for this is that the recruitment of the Central School teachers is done in Delhi while we ourselves recruit teachers for the Campus School. I only hope the support from the government continues. We have been lucky in having an excellent coordinator in Mr. Gupta. He has proved to be a valuable asset for the school, and we hope that we will be able to keep him.”

PKK wanted the control of the decision-making process of faculty appointments both for the Institution as well as the Campus School to remain within the Institute. He valued the commitment of the faculty and staff to IITK and encouraged participation in the excitement of building an institution from the start.

Comments by Colleagues

The late Dr. Oliver Dunn, Associate Director, Purdue University Libraries, had this to say about PKK: “I have never known anyone quite like him and will always think of him as an outstanding figure in the field of University education. He was so gentle and at the same time so powerful in thought and influence. It was a great privilege to be associated with the institution that he founded and guided for 10 or so years.”

Mrs. Irma Johnson, a Science Librarian from M.I.T., wrote that as is typical of a true educator, PKK supported the library. He understood the importance in an academic library of good liaison with the faculty: that an academic library serving tomorrow’s leaders would be more than a collection of books and technical reports. “In him, I felt I had met a spiritual quality that India had been known for in the rest of the world; and so, in retrospect, I was glad to have the opportunity to serve the Institute close to three years during Dr. Kelkar’s tenure. I believe that IITK was indeed fortunate that Dr. Kelkar was the founder and its first Director.”

PKK’s sensitivity to students’ needs and sentiments is illustrated by the following anecdote related by one of the students of IITK. A group of students had gone to an N.C.C. (National Cadet Corps) camp in a remote place where the students were totally isolated from the world of media. A rumor was started that a famous cinema actor, Dileep Kumar had died. There was no way to verify the rumor, and students were very restless. Somehow PKK learned about the rumor. When PKK visited the camp that evening, the first thing he did was to reassure the students that it was not true. Mr. Dileep Kumar was alive and well and that revelation elicited many of sighs of relief.

The Dahls – a lifelong Friendship

Norman Dahl and my father first met in January 1961. Their friendship continued even after they were no longer with IITK. They both independently said that they had never had such a meaningful working relationship ever in their professional lives. They always addressed each other formally despite their close friendship. The families still continue to be friends.

In a letter to PKK dated August 31, 1964, Dahl says, “We did not realize until we arrived home in Lexington, how completely we had become involved in the IIT and in the lives, hopes, and aspirations of all of you. It is taking considerable conscious effort to focus on what is ahead here rather than what is behind us in Kanpur. To say that we miss you and Mrs. Kelkar is the most important adjustment we have to make. One reason why I have delayed so long in replying to your letter of 4th August is, I am sure because of my resistance to accepting the fact that we now must communicate by letter rather than by talking. Now that I am past that point, I feel a certain relief and look forward with anticipation to this new phase of our relationship.”

In reciprocating Dahl's feelings, PKK in his letter to Dahl dated October 4th, 1964, says, “As it is I am late in replying, and you will hardly realize how many occasions I have missed really wanting to have a talk across the table. I am afraid freshness of impact will always be lost, and I will have to concoct letters in cold blood. This means time will drag on and I can never be certain of writing when I ought to. All the same this is the only way of communication left. We must make the best of it.”

Later in the letter PKK talks about budget restrictions in the selection of faculty. He says, “The kind of freedom we had on the last two occasions when we were selecting faculty will not be available to us this year. Nevertheless, I have decided to go through the selection process as though we have complete freedom, and then depending on the number of candidates available, fight for more positions if that becomes necessary before actually sending out letters of appointment. Let me see how far I succeed. The sad part of the whole situation is that none of the other four institutes have the same problem. There is very little sympathy as a result of this.”

“When I look back, I very often feel that last year we had a dream element associated with whatever we attempted. Deep inside there was a feeling that even frustrations and compulsions were a part of the process by which a dream becomes a reality. I am afraid it is difficult to sustain this feeling any longer. There is no doubt at all that the Institute is growing and progressing in many directions. Nevertheless, I am finding that it is easy to feel a complete outsider even though one is right in the midst of it. After all, I must be aware of my limitations which are far in excess of my aspirations. In spite of this, I do hope it will continue to be an exciting job.”

In reply, in his letter dated January 5th, 1965, Dahl says, “One of the puzzling facts of my life right now is my difficulty in understanding why I think so often of Kanpur and yet find it so difficult to write to you. Perhaps this is because I am unwilling to accept reality that, in fact, is the only way we can communicate and that the luxury and pleasure of talking face to face is in fact no longer available to us. I know that you, too, are undergoing a similar experience. Much as I may seem concerned with my own sense of lack, I think I can appreciate your condition since I do know that anyone carrying the burdens you do must have someone with whom you can frankly share these burdens and one of the great pleasures of my years at Kanpur were these mutual explorations that went on verbally. Perhaps with time we will be able to make script do what sound once did.”

In his 10th February, 1965, letter to Prof. Dahl, PKK says, “Since March 1962 until May 1964, my involvement in the interaction between KIAP and IIT had become for me almost a way of life. There were several threads that were tied together, and a pattern was emerging that looked as though it could in time to come evolve itself into a significant form. I cannot avoid the feeling that the threads have broken and the pattern is changing. Perhaps this is as it should be and is all for the good. All said and done the Institute is far bigger than any of us individually speaking. There is vitality, there is growth, there is turmoil, and every now and again elements come to the surface that are characteristic of a first-rate institution. There is, however, a feeling of disjointedness indicative of the autonomous nature of various forces present. The working of the system is becoming so different that I do not get the feeling that I am participating in an organic process of which I am an integral part. Now and again I wonder as if I were an outsider. I have realized that continued intellectual and emotional sharing of an exciting experience can lead to an addiction even more compelling than that of a drug. I must confess that I feel very often lost and alas! I can find no substitute. What I had imagined to be just an end of a chapter seems to be more like an end of a book. I talk to others of adaptability to quick change, and now for a ‘change’ I have to talk to myself about it. Things indeed are different from what they were.” PKK felt the fascinating alchemy of intellectual and personal sympathy in the Dahls and that this colored his subsequent experience at the Institute.(9)

In the same letter PKK continues with these remarks. “The computer conference was a great success. It most certainly had an intellectual content and the kind of drive which seems to be characteristic of those who are ‘wedded’ to the computers. For me it was an opportunity to learn many things, and I once again became convinced that the computer represents the future far more significantly than any other device I have known. The whole of December was a month of visitors, conferences, and courses. The general results have been good and gradually IIT Kanpur is having its impact on an all India basis. It looks as though many people have to hear about IIT Kanpur in spite of themselves and they are inclined to write it off as propaganda. Nevertheless, I have a feeling that the kind of things we are attempting has created an atmosphere in the Institute which affects people who visit us as something which is charged with enthusiasm and freedom to experiment even to the extent of making mistakes. I am afraid there is every danger of our reputation running faster than our achievement. I sincerely hope we are not caught on the wrong foot. I feel really frightened sometimes.”

PKK describes his feelings to Dahl after a visit to the US in a letter dated August 31, 1966. He says, “As I look back in time, the memory of every association with you comes back to me. All these associations have now acquired a quality of simultaneity, and they seem to fit together as though they have been brought to life on a canvas by a great painter or an artist who might even be a musician of distinction for all I know. Echoes can be visible as also audible. Weekend in Lexington, visit to Princeton, a fortnight in Cambridge, Mass., a meeting in Washington - they all come back to me. Feelings and ideas shared informally between individuals sometimes give rise to insights which make it possible to have a better understanding of the larger environment which provides the background. The whole process seems to be effortless, natural, enjoyable, and often exciting, and yet it somehow seems to involve something at a very much deeper level. That is perhaps why this type of experience becomes a part of oneself and has a continuity which is akin to life. A reference, an incident, a phrase, a look and many such apparent trivialities become as evocative as rain, wind, sea, and earth. In this context I do not even know how to express my feelings of gratitude towards you and Mrs. Dahl. At the risk of being misunderstood I wish to say that because of my association with you and Mrs. Dahl during this visit that I feel I have acquired a new and deeper understanding about the United States. That is perhaps why I have instinctive sympathy for late starters. After I returned from the States, the most powerful impact on me was the realization of how enormous the gap is between what ought to be and what can be. The basic need for IIT Kanpur is to embark on a vigorous and steady recruiting drive to increase the size of the faculty. I am afraid I will have to go through several stages of persuasion before I am able to get a sanction for the kind and the number of positions we need desperately. During the last two months it has become clear that the majority of the people we have here are capable of making contributions not only towards teaching and research but also in a wider sphere in relation to education and industry.”

It is apparent from these letters, reinforcing the strong ties of friendship that the Dahls had formed with PKK, that they had become a surrogate family, especially on an intellectual level, even after they left India in 1964. It was difficult to deal with their absence as PKK’s own family was not in IITK. The reference to ‘late starters’ tells us that he was always intellectually curious and the discussions and correspondence with the Dahls satisfied his intellectual needs.

The decade between 1960 and 1970 was challenging and rewarding for those who participated in building the institution. PKK observed in his 1981 convocation address that, “Students of the first batch who joined IIT Kanpur were the real torchbearers of its Spirit, which they passed on to the generations of students who followed them.”7 He further noted that the first class had joined the Institute when it had virtually no resources and that the faith they had shown in the future of the Institute was a great source of inspiration. In his view, these students represented the future and would be much more representative of the Institute’s future direction. Along with the pioneering faculty members, the students of the first three batches had witnessed the exciting arrival of the IBM 1620 computer, which had been transported on a bullock cart from the airport. Having one of the first computers in an academic institution in India, the IITK computer center became a national resource by the early 1960s. Apart from required undergraduate courses, the center conducted a number of two-week or longer courses for outside participants. The center’s national prominence attracted many well-known visitors including Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

PKK in his December 14, 1977 reply to Prof. Norman Dahl says, “The political environment [in India], and the confrontation of stark disparities make it difficult to feel either enthusiastic or optimistic. Even so, one does feel sometimes that something useful can be done. I am convinced that there is no substitute for natural goodness or kindness. But then it is equally true of natural wickedness or cruelty. Conviction is a source of strength while doubt is a source of weakness. Life all the while consists of both, and one is tempted to call it predestination. I sometimes flatter myself that we two - yourself and myself - were in a way responsible for writing the ‘genetic code’ of IITK from 1961-1964, to a large extent. Nothing has baffled me so much as the unfolding of the code during all these years. In spite of everything, I feel those three years of my life were perhaps the most significant and memorable. It is superfluous to say, Thank you so much.”

In his letter to Dahl dated June 12, 1981 PKK says, “We were literally in a ‘dream world' for the four days when we were in Kanpur. We met through the ‘eyes’ as if - the trees, the lawns, the corridors (in spite of the outer wall), the very air we breathed seemed to ‘whisper’ deep inside the message that the golden dawn has lit up the horizon announcing the beginning of a New Chapter for IITK. ‘History’ has taken in hand ‘IITK’ once again to make it play the role assigned to it in making the silent but inevitable revolution which is literally churning this country. All in all, for the first time during the course of the last ten years or so, I feel optimistic about the future of IITK. Both you, and Mrs. Dahl were as if with us during our stay in Kanpur perhaps because of your recent visit.”

In his letter to Dahl dated April 3, 1984 PKK writes about what he thinks is important to think about during the ‘Silver Jubilee’ year at IITK: “To my mind the most important task of the whole Jubilee year should be an appraisal of -: a) When we started the IIT what was our Vision, what instruments we fashioned to give substance to our Vision, how the ‘motivation’ and ‘inner urge’ of all those involved was sustained, and finally, what made it possible to keep a count of the ‘individual trees’ without losing sight of the forest as a whole. b) What role the continuous exercise of impartial discriminations play in generating individual motivation, creativity, and the urge to do something without disturbing the overall balance between conflicting situations, diverse personalities, and individual and collective grievances. c) What exactly is the reality on the ground today and how does it match with the original Vision. d) In spite of our best efforts, fruitful teamwork on the part of the faculty has not materialized to any extent. On the other hand, teamwork between an enthusiastic faculty member and a group of equally enthusiastic students has shown spectacular results. This dichotomy needs probing. e) By all accounts it seems the ‘climate’ of IITK is such that the students who come out year after year have attitudes and a unique competence which distinguish them from graduates not only of other institutions but also of other IITs as well. They are not overly burdened with ‘conventional wisdom’. They are willing to face any problem cheerfully and jump into entrepreneurship to seek solutions to problems --scientific, technological, managerial, or what have you. One of the elements which is responsible for the student success is that there is still a ‘critical size’ of faculty members who not only guard ‘academic values’ from being diluted, but also by the quality of their academic work have kept up the prestige of the Institute.” PKK felt that for an Institution to continue to excel it is necessary to undertake a periodic self evaluation by people who feel a kind of a call from within and act like men possessed. This indicated that the evaluation would need to be performed by those with deep commitment to the institution. Further, he talks about other academic institutions like Banaras Hindu University and Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore saying he believes that an Institute is really great when the academic climate makes it possible for even second class individuals to be inspired to do first class work. In this context he recalls a Sanskrit saying. “There is no ‘root’ of a tree, or a shrub, or a plant which has no medicinal properties; there is no letter of the alphabet which cannot be made to become a carrier of a spell; there is no individual for whom nothing useful to do cannot be devised; but the individual required for this purpose is hard to find.”(10)

Referring to some of the work done by Norman Dahl at MIT, PKK says in his letter dated July 28, 1976, “The amount of work you have gone through must be a rewarding experience for you. It had the effect of blowing off some of the ashes and rekindling dying embers so far as I am concerned. I have always believed in the power of words, and I have been fascinated by the seminal quality and ability to release hidden sources of energy locked up in all kinds of human beings and in all kinds of circumstances. Words can become spells, carriers of magic, or a door of perception and deliverance. And yet there is no single language. Technology is imposing some kind of common language. But then the words that really count have the same message no matter what the language. What we actually hear and see is the flux of life momentarily illuminated in a patch here and there. Walden and Ascent of Man give the backdrop. The reference toWalden(Thoreau, a poet-philosopher of nature) and Ascent of Man (Bronowski, a mid-century anthropologist) give the backdrop to PKK’s philosophical approach towards communication. Judging from this, it is not surprising that PKK called himself a ‘purveyor’ of words.

I have reproduced a substantial amount of the correspondence between PKK and Dahl, because I do not know a single individual who became better friends of PKK than Norman and Dorothy Dahl. Judging from the letters, the admiration and affection were mutual. In spite of not being on first name terms the relationship remained very close until the end. My husband’s, my sons’, and my relationship with Mrs. Dahl continues to be close to this day!

Director of IIT Bombay

PKK returned to IIT Bombay in 1970 as Director, replacing, Brigadier S. K. Bose who went to IIT Kharagpur as Director. It was more difficult to make changes in IITB than had been the case in IITK, which he had shaped from the outset. Here are some of the observations made in Dr. S.P.Sukhatme’s book titled “Four Decades at IIT Bombay.”(11) Sukhatme thought PKK was in some sense a visionary. PKK had a philosophical outlook and a tremendous feel for education. To him, education meant a rounded individual, not learning a subject here and there. It meant a person, who while being an engineer had a broad feel for the humanities and the sciences. Humanities and Social Sciences were to be taught for their own sake as beautiful subjects and then, of course, engineering subjects were taught first as science and then as an art. To him this was education. In a sense, this is the guiding philosophy of many of the world’s best universities. PKK believed in this passionately. This vision had been implemented in IIT Kanpur, and he also wanted this to happen in IIT Bombay during his four years there. Policies that were in place at IITK such as the semester system and the special curriculum were unique for an engineering institution at that time. PKK wanted all these things to happen and he could see immediately that this would also require a change in the structure of the academic bodies at the Institute. In order to get things moving in IITB, PKK appointed a high level Senate committee. The committee circulated a questionnaire, then consulted many faculty members and presented its report to the Senate in a few months. Basically, the committee agreed with PKK's thoughts on the required changes. The other two committees were the Rules Committee and the Curriculum Committee.

According to Sukhatme the procedure followed by PKK was a good example of the approach to be followed for tackling a complicated issue involving a major change to an existing system. “Never try to go into the details first. First secure an agreement in principle to the broad outlines of what you want done. This way, you have the Institute committed to something; then appoint a committee or committees to work out these details. When you recall these events in perspective, you begin to appreciate the person's art in getting things done.” Sukhatme was a member of both the committees. The committees were formed in March 1972, and PKK wanted a beginning to be made in July that year. The committees got their approval from the Senate, and from July 1972, the semester-based system was introduced. PKK was a respected, senior figure. In the Senate, he presented his arguments for change so convincingly that he could get things done. Variations have been proposed at a later date to the grading system and continuous assessment. But the essential features have remained the same. PKK was able to effect these lasting changes in a short span of time. PKK also created the positions of Dean of Academic Programs and Dean of Research and Development.

In a span of four years PKK did many things that have influenced the Institute in a remarkable manner. During PKK's tenure the scope of the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences expanded from six faculty members to fifteen or sixteen faculty members. According to Sukhatme, PKK’s way of doing things was always to speak politely. There was never any unpleasantness in what he said. His way of speaking was refined, and even when he was annoyed, you had to understand his language to know that this was the case. At times PKK could be ambiguous. If one sent him a note requesting permission to serve on some committee outside the Institute or to do some work for an outside agency, the note would come back with his initials PKK written on it in big letters and nothing more. When Sukhatme asked a colleague what it meant he said, “If the note comes back with PKK's initials, it means he has approved your request.”

Through his work in IITB, he established contact with industrialists and research leaders in Bombay. PKK retired from IIT Bombay in 1974.

Honors and Awards

Towards the end of his distinguished career, PKK was honored for his achievements in India and worldwide. In honor of his contribution to technical education, the Government of India conferred the title of Padma Bhushan on him in 1969. He was elected a Fellow of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, London U.K., and of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore, India. In 1981, IITK conferred upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Science. The recognition of his achievements also led to a number of significant administrative positions. For example, he served as President of the Commonwealth Inter-university Board of India in 1969 and was also a member of the Sarkar Committee of the Government of India for reviewing the CSIR (Council for Scientific and Industrial Research). In addition, he was on the governing board of the Institute of Science, Bangalore, India, for many years.

PKK’s public addresses during this time also highlighted his commitment to addressing the economic and educational imbalances between developed and developing nations. In 1968, he was asked to give a talk at the conference on “The Role of the Professional as an Agent of Political, Economic, and Social Changes in Low Income Countries” organized by the University of California, Berkeley. The title of the paper he presented was “Establishing a Technological Institute, with Special Reference to KIAP.”

In 1971, The Institution of Electrical Engineers, London celebrated its centenary. PKK was one of six speakers invited from throughout the world and read a paper titled “Disparate World – Challenge to Education.”(12) The paper was very well received by the audience and by people in India.

My Personal Reminiscences of My Father and Our Family Life

My father’s notable achievements were in the field of technical education. It was possible for him to devote himself completely to this task because the responsibility of our extended family was borne by my mother. When my father shifted base to Kanpur, my mother had to remain in Bombay to take care of my ailing grandfather, as well as to be with me till I had finished my Masters’ course. Even after my grandfather’s demise she often had to be in Bombay while he was in Kanpur. She was thus looking after two households. In addition to this, she made it her mission to find me a suitable husband, which kept her away from Kanpur even more.

Despite his career in the public sphere, my father was an introvert and given to private contemplation. Being extremely well read he often claimed he “had a thousand books at the tip of his tongue.” Although he did not spend a great deal of time at home, he often entertained his children with imaginative stories involving an original cast of characters. He was fond of wordplay and developed an unusual vocabulary, and made witty comments or observations among family members.

My father spoke our mother tongue Marathi fluently, but was more comfortable speaking in English. As children he made a number of children’s books available for us to read mainly in the English language. He left our Marathi education entirely in the hands of our mother, who was a stickler for use of correct and polite language.

My father thought it was necessary to learn French before he visited France in 1956. He purchased a set of Lingua-phone gramophone records (78 rpm) and set about learning French. As children, - it was fun for us to listen to the records and that was my first introduction to authentic conversational French.

Although my brother and I are the only children of P.K. and Krishnabai Kelkar, due to various circumstances four of our cousins came to live with us, and we grew up as a group of six children in the household. My mother was the main disciplinarian and my father was called upon to help only for more serious matters.

One of the fondest memories of my father is the day my fourth or fifth birthday was celebrated. My brother and I were dressed in silk outfits made from my mother’s old sari. There were about six or seven children who were present. We had the usual balloons, games, and food (shreekhand and puri), which were arranged for and overseen by my mother. The highlight of the day was a film screening. My father had specially arranged to have a friend Mr. Karandikar over with his eight-millimeter film projector. We all giggled and laughed during the films of Laurel and Hardy and Charlie Chaplin.

While I was growing up, my father was a professor of electrical engineering at the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute (VJTI). He preferred to go to work around 10:00 a.m. He took his time getting ready in the morning, always impeccably dressed with a dab of eau de cologne (the original 4711 being his favorite), and being a person of faith he spent an hour in prayer. Some days he ate lunch at home before going to work. We were always hovering around him to get a crispy part of the chapatti, which we called ‘biscuit’. After parting with most of his chapatti not much was left for him, but he never complained.

When the children of our household were teenagers, my father arranged a competition for all of us. First was a memory game, - where objects were displayed around a room and we could look at them for two minutes. We were asked to recall all of them and the person who remembered the most number got a prize. Among the other games, two are particularly vivid in my mind because I won them. The first was a game to recognize different smells. Having spent time around the kitchen and garden, it was easy for me to recognize the fragrances and odors. The other contest was a voice contest where we were expected to sing several songs in tune and my cousin and I won. Normally we listened to the radio, played board or card games, or played outside on our own. The contest was something special because parents were involved in planning entertainment for us.

My father had a few good friends who came to visit from time to time, but I never heard him address any of his friends by their first names. Only cousins, children, nieces and nephews were addressed by their first names. A few of his friends’ children have mentioned that he made a special effort to listen to their side of the story, or would take them out when their parents were not available, and was considerate of them in general. We would feel somewhat envious when other children were taken to games or shows when special passes were available, but we could not go because it would smack of nepotism.

Astrology was one of my father's favorite hobbies. There was a group of people he associated with only because of his love for astrology, and some came to ask his advice based on astrology. Among our guests there were some astrologers as well. When I grew up and was taking a long time to get married, my father had stopped looking at horoscopes for a while. After I married, I often asked him about our future prospects of getting the right job, the right house, etc. He would give answers that made us feel more hopeful. Astrology was strictly a hobby of PKK and did not interfere with his professional life.

My father was fond of English literature. I had to study “Merchant of Venice” in an abridged version for my 10th grade English exams, but he read the whole text with me and was very strict about how I pronounced the Italian names. I was getting nowhere, and the beauty of Shakespeare was lost on me. It was so much easier to study with my mother, even if the subject was Arnold Bennett’s rather dry essays. She was more sympathetic to our lack of knowledge of English as it was our secondary language. It was possibly because of this lack of literary talent that I chose science subjects for my undergraduate degree.

Just like English literature, my father loved physics. It was a different experience when he taught me Maxwell’s equations when I was studying for a degree in physics. He was a lot more patient with my inability to understand the dot and curl products of the vectors than he was with my lack of appreciation for literature. When I finished my masters in physics I went to IIT Kanpur to stay with my parents. I joined the physics department as a research assistant with late J. Mahanty.(13) The next year my brother finished his undergraduate degree in Electrical Engineering from Benares and joined IIT Kanpur as a student of Masters in Electrical Engineering.

For the first time, in 1966, my parents and their two children were together as a nuclear family after a gap of almost 20 years. Very often the family discussion would be dominated by my mother’s worry about my not getting married like all other friends and relatives’ daughters. She genuinely believed that it was my age and complexion that were the cause for the delay. I am grateful for my father’s faith in my desirability in the marriage market. He would often point this out to my mother, giving her examples of the type of son- in- law he/she would not like.

All this pressure at home and lack of a great academic performance made me and my brother feel somewhat inadequate in the shadow of my father’s name and fame. My mother’s frequent absence from IITK made her feel as if she did not perform the role of the director’s wife as was expected of her. In spite of our inability to shine, what my parents gave us was pedigree and a sterling set of values that my brother and I have tried to pass on to our children.

My father inculcated the love for western classical music in his children. My parents regularly listened to All India Radio for both Hindustani and western classical music. When time permitted, out came the old-fashioned gramophone on which we heard symphonies, opera, and some light classical music from Indian films. We never did graduate to appreciate opera or enough of Hindustani music to be able to recognize the ‘Ragas’. However, all that exposure has certainly paid off as we appreciate classical music even more now than when we were young.

Sports was not a strong point in our family, although my father did try his hand at tennis, and perhaps cricket. But he preferred to talk about sports more than engage in them and express opinions read in print. What he loved most was to discuss politics, science, literature, and philosophy with his intellectual peers. He appeared to be more interested in philosophy of science and engineering than the actual practice of the subjects. Since India was a developing country, PKK was always interested in intermediate and relevant technology of the cottage industry type.

Unfortunately, we never talked much about his childhood. He lost his mother at an early age and though he had two younger siblings he was basically a loner. He was fascinated by words, mainly in print but also in films, broadcasts, and speeches. Books appeared to be his closest friends. He was convinced that science education was the ticket to future progress, and he advised his cousins and his children to study science for their undergraduate degree. I chose physics only by a process of elimination and not by one of selection. I continued to study it, but physics seemed less relevant to my life than a subject such as psychology, which, by the way was my mother’s first love. My father always supported what I wanted to study, but it seemed impractical to switch the direction of my education after completing my undergraduate degree.

My father’s favorite journals were The Punch, New Statesman and Lilliput, all of which were British publications. He avidly read the book reviews from the ‘Statesman,’ and based on those reviews sometimes ordered books for himself. He recommended buying books for the libraries where he worked if he thought they would enrich the collection of that institution.

Headaches were a constant irritant for my father. Since the ill effects of aspirin were not known at that time, he always depended on Aspro (local brand of a compound of aspirin) very often. Whenever he was under stress or was getting ready for a speech, he often suffered from colitis and was in excruciating pain and had to resort to a bland diet. I wish he had taken better care of his health. As I have said before, he was not athletic and his activity level went down even further with age.

One of my favorite activities with my father was to total the points on all graded papers. He used to be an external examiner for different universities. I not only enjoyed adding the total marks but also enjoyed using the red and blue pencils, which we were not allowed to touch as a rule.

What My friends remember of ‘Kelkarkaka’

This is a collection of memories as related by Mrs. Vidya Paranjpe, daughter of Kelkar’s close friend, Dr. G. P. Kane. She says, Kelkarkaka, as she called him, was always having discussions with her father at the dinner table on many of his frequent visits to Delhi. She was awe-struck by the fact that PKK was one of the few people who would disagree with her father and tell him if he was wrong, and her father took it. She remembers PKK as a fine human being given that he was a well-respected and successful person professionally, and she will always have a special place in her heart for Kelkarkaka.

Another family friend Dr. G.M. Nabar’s son, Dr. Vikram Nabar said that PKK was always ready to treat children with respect and not tattle on them even if they were wrong. To this day Vikram remembers an incident when he forgot to give an important note to his father about a meeting Nabar, Kane, and Kelkar were supposed to attend. Kelkar’s reaction to that was very different from Kane and Nabar’s, who were not too pleased. Vikram would like to emulate Kelkar's manner in which he treated all children.

Dr. Anand Nigudkar from Pune has been our family physician for many years. On one occasion PKK needed medical advice while he was in Pune on business. PKK was at Dr. Nigudkar's office waiting patiently for his turn. Dr. Nigudkar offered to see him before all other patients and PKK refused. He said those patients have been waiting for a long time, you take care of them first. Dr. Nigudkar was touched by this display of fairness.

My other friends Dr. Thailamani Iyer and Mrs. Rashmi Bidnur had a similar experience of how considerate and hospitable Kelkar was, irrespective of whom he was welcoming. Rashmi became a frequent visitor to my parents after I was married and had left for the US. Rashmi remembers how PKK enjoyed the small pleasures of life, like savoring a snack sold by the street vendors, and at the same time when she needed professional advice, or an astrological prediction, he was there for her.

My cousin’s wife, Kunda Kelkar, remembers him as a gentle person, who never rebuked or asserted his own point of view, always allowing the other person to follow his or her own path. Though he was the head of the family, she never felt any pressure of expectations from either him or my mother (being a daughter-in-law of the house). They were both extremely kind. Once when she was convalescing from a long illness and staying with my parents at IIT Bombay, they were all to go to a dinner party. Kunda, a lecturer in German, was feeling out of sorts, but he immediately cheered her up when he saw her dressed up by saying in perfect German, “Welch ein huebsches Bild” (“What a pretty picture!”) She remembers how he encouraged her culinary efforts by suggesting how to make her preparations even better. They would sometimes discuss Hindu philosophy and he bemoaned the fact that it was so ill understood in the West.

The last years

After retirement my father settled down in Matunga, Bombay, but continued to serve on a number of governmental and educational committees. He visited the USA to be with his children three or four times. Eventually, his health deteriorated in the last five years of his life, and he passed away on October 23, 1990, at the age of 81.

It was during his retirement that my father decided to write his memoirs. Mr. H.T. Shedge, a retired staff member from VJTI, helped him type the manuscript. PKK was not comfortable with the use of the computer. Shedge remembers how PKK treated everybody with the same respect. He particularly remembers his knack of explaining a difficult subject to people unfamiliar with it with the greatest care. He would use different examples to make sure the idea was very clear to the person listening to him. He had a great desire to tell the world about a lot of things which remained unsaid due first to ill health and then his passing away.

What I have put together here is based on material written by his colleagues, material gathered in conversations with family and friends, and material from my father’s correspondence. Aside from his professional achievements, I hope this biographical sketch gives a glimpse into his personality as a friend, as a father, through his daughter’s eyes.

References:

-

Bombay Presidency From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the British East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.

-

A.R.T. Char, Professor and retired as Head of the Electrical Engineering Department, V.J.T.I. Bombay (1950-1980).

-

Dr. A. S. Dighe, Professor of Mechanical Engineering V.J.T.I. (1957-1958, 1960-1967) and University Department of Chemical Technology (1967-1969, 1973-1975). Retired as Senior Engineer at Tata Power Co. ,Bombay (1975-1994).

-

A.S. Parasnis, Professor of Physics, IITK, 1960-89 and a close associate of Kelkar, in “IITK, Kelkar and I” p.2

-

Mr. A. P. Kanvinde of Architectural firm Kanvinde, Rai and Associates.

-

Excerpts from P. K. Kelkar’s convocation address May 17,1981.

-

IIT Kanpur Silver Jubilee Souvenir, 19.

-

Kanpur Indo-American Program report by, Norman C. Dahl

-

“Dr. P.K. Kelkar (1909-1990)” by Dr. A. S. Parasnis p. 9.

-

The source of the original Sanskrit Sloka is not known.

-

“Forty Years at IIT Bombay”, Dr.S.P.Sukhatme.

-

Disparate World, Challenge to Education, by P.K. Kelkar, presented at the Centenary celebration of Institution of Electrical Engineers, U.K. - now known as The Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET), London, U.K.

-

J. Mahanty Prof. of Physics IIT Kanpur, 1962-1972.